When Michelle Stecher was born 33 years ago, her doctors were at first unsure what to do for her. What was first thought to be a heart murmur was, in fact, a congenital heart disease diagnosis that was staggering in its complexity:

When Michelle Stecher was born 33 years ago, her doctors were at first unsure what to do for her. What was first thought to be a heart murmur was, in fact, a congenital heart disease diagnosis that was staggering in its complexity:

- Atrioventricular septal defect – holes between the chambers of the right and left sides of her heart.

- Total anomalous pulmonary venous return – all four of her pulmonary veins did not connect normally to the left atrium but instead drained abnormally to the right atrium.

- Pulmonary stenosis –narrowing from her right ventricle to her pulmonary artery that obstructed blood flow.

- Transposition of the great arteries – her aorta was connected to the right ventricle and her pulmonary artery was connected to the left ventricle – the opposite of a normal heart.

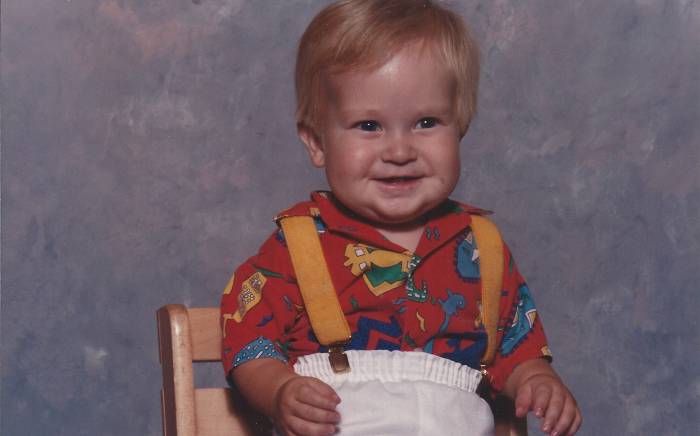

“Basically, the doctors told my parents to take me home and love me until they figured out what to do,” says Stecher. “My parents did that, but they also encouraged me to be a kid. They told me I’d know my limitations. So when I was running and playing with my friends and got winded or tired, I just stopped.”

At age 3, Stecher underwent two surgeries performed by cardiothoracic surgeons at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. The final result of the Glenn and Fontan procedures was a single-ventricle repair that sent oxygen-poor blood returning from Stecher’s body directly to her lungs, bypassing her heart.

“I did really well after the surgeries. The surgeons found that encouraging, but they told my parents to monitor me,” says Stecher. “Thankfully, my parents’ attitude toward me as a child living with congenital heart disease didn’t change. They treated me like any other kid, which meant letting me do the things I enjoyed.”

For Stecher, those things included playing soccer and softball. “My first soccer game I was playing defense and being pretty aggressive, hip-checking other players,” Stecher recalls. “It wasn’t until three games in that my parents told the coach I had a heart defect. They didn’t want the coach to treat me any differently than the other players.”

As an adult, Stecher has completed two half marathons—the most recent in May 2018, 30 years after her first surgery.

As an adult, Stecher has completed two half marathons—the most recent in May 2018, 30 years after her first surgery.

Transitioning to adult cardiology care

Stecher continued seeing pediatric cardiologists at Children’s Hospital until she was 20, when she transitioned to adult specialists at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. She continues to receive annual check-ups through the Washington University Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. The program was among the first in the country to earn accreditation from the Adult Congenital Heart Association.

Specialists at the Washington University Adult Congenital Heart Disease Center believe there are currently more adults than children in the United States living with congenital heart disease. Adult patients with congenital heart disease can develop additional complications as they grow older. For that reason, it’s imperative that pediatric patients transition into an adult program specializing in their disorder.

Among the complications that can develop are problems involving the liver, peripheral circulation and blood clotting. In addition, young women who are followed by an adult congenital heart disease program benefit from counseling about contraception and pregnancy.

Research data show that less than 30 percent of pediatric congenital heart disease patients transition to an adult provider. Amy Mueller, RN, ANP-BC, a nurse practitioner in the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program, is working to increase that percentage for pediatric patients at St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

“I talk with patients in their mid-to-late teens about our program and why it is important for them to continue seeing an adult cardiologist specializing in their disease,” she explains. “It’s important that they begin taking responsibility for themselves, which means learning how to make their own doctor’s appointments and filling their own prescriptions. I also work to ensure they understand their anomaly, the surgeries they’ve undergone, their medications and possible side effects, and for women, the risk should they become pregnant. Many young women have been told they can’t have children—that is not always true.”

She adds, “We realize these patients are extremely attached to their pediatric cardiologists. Our goal is to reassure them that we work in partnership with their pediatric providers.”

A future dedicated to inspiring others

After completing a bachelor’s degree in psychology and then working as a preschool teacher, Stecher decided she wanted to do more. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in nursing and now works at St. Louis Children’s and Washington University Heart Center.

“I know what it’s like to live with a chronic disease, and I love kids. I understand these families who want the best for their children because it’s what my family wanted for me, too,” she says.

“I am among the first generation to survive this long with congenital heart disease. I want to help the next generation realize that they can cope with this disease and strive to achieve the best-possible life for themselves.”