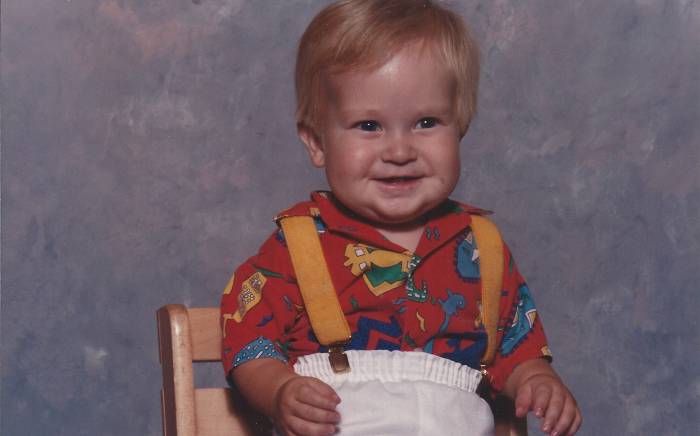

When Kelsey Beelman was 2 weeks old, her pediatrician heard a heart murmur. “My parents knew it wasn’t good when the doctor came in with a serious look on his face, shut the door and said, ‘I never would have known your daughter would have had so much wrong with her by just looking at her,’” Beelman says. “I was a healthy, normal looking body on the outside, but not on the inside.”

Beelman was born with a single ventricle in her heart which effects blood flow to and from the heart.

In 1993, two months before she turned 3 years old, a physician at St. Louis Children’s Hospital performed the Fontan procedure, an open-heart surgery for children with univentricular (one ventricle) hearts. After the Fontan procedure, the blood from the lower body goes directly to the lungs. The blood with high oxygen goes into the heart. This way, the single ventricle only pumps blood with high oxygen to the body and there is no more mixing of oxygen-rich blood and oxygen-poor blood.

Beelman is grateful that, as a congenital heart disease patient, this was the only surgery she has had her entire life.

Besides getting exhausted a lot faster than others, Beelman hasn’t had any major side effects throughout her life. “I was able to play softball as a child and running short distances was all I could manage,” Beelman says. “I really did have a normal childhood.”

When she got married, she wanted to have children right away because she wasn’t sure how that would affect her heart.

“I love children,” Beelman says. “I was a nanny for many years and really wanted to have some of my own. I asked my cardiologist if I would be able to have children and he wasn’t sure how my body would handle it because every case is different.”

Beelman started trying to get pregnant right away after getting married and had some problems getting pregnant, so after a year she and her husband went to a fertility specialist who did all the appropriate tests and couldn’t figure out why she couldn’t get pregnant. She thought it had to do with her heart, that the low level of oxygen in her body could be suffocating the sperm.

After discussions with the fertility specialist, Beelman and her husband decided to try intrauterine insemination (IUI), a fertility treatment that involves placing sperm inside a woman's uterus to facilitate fertilization.

“On our first try, I did become pregnant, but lost the baby at eight weeks,” Beelman says. “I tried IUI several more times, got pregnant three times but lost the baby each time. It was so heartbreaking — I was not meant to carry children.

“I decided to try one more time and on the seventh try of IUI, I was able to get pregnant and stay pregnant,” Beelman adds. “It was reassuring at my first ultrasound that the baby looked good. I was so relieved.”

Beelman says it was an easy pregnancy with no complications. Regular growth ultrasounds were conducted to monitor the baby’s growth. “She was measuring small,” Beelman adds, “but the doctors let her grow at her own pace.”

A C-section was planned for 37 weeks, but Beelman ended up having it a few days earlier. “My daughter was born weighing 3 pounds, 9 ounces, and had to spend about 12 days in the NICU,” Beelman says. “I was admitted to the ICU for 24 hours to monitor my heart and my blood pressure was high and I was given medication to treat that and was so sad because I couldn’t see or be near my daughter that entire day.”

Kathryn Lindley, MD, Washington University cardiologist at the Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Heart & Vascular Center, who specializes in pregnancy-related heart disease, followed Beelman after her delivery to make sure her heart was doing okay.

Once Beelman’s daughter reached 4 pounds, they were able to go home. “She was a perfect, healthy baby," Beelman says.

Six months after the delivery, Beelman had an echocardiogram (ECHO) done of her heart and the doctors said everything looked good.

“The doctors told me I needed to wait at least a year until I tried for another child, but sometimes life throws you a few surprises,” Beelman says. “When my daughter was 13 months old, I found out I was pregnant. It was a complete shock to me and my husband and a true miracle because of how hard it was for me to get pregnant the first time.

“We did the same thing with our second daughter,” Beelman says. “We had growth ultrasounds regularly and another planned C-section. My daughter weighed 4 pounds, 9 ounces, a whole pound more than her big sister. I was able to have a normal experience with her. She didn’t go to the NICU and I was able to hold her the day she was born. We were blessed to have another beautiful, healthy baby girl.”

But, about eight days after the delivery, Beelman noticed some chest pain and immediately went to Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “After many tests, the physicians confirmed I had a blood clot in my lungs and behind my heart and fluid in my lungs. The physicians tried a different number of medications to get my heart under control and I stayed in the hospital for three days and then was able to go home to my girls.”

Beelman had another ECHO of her heart done about a month later and everything looked good.

“I am feeling really good and healthy,” she says. “My 18-month-old and 3-year-old definitely keep me busy. I am very grateful to all the physicians who helped me during both of my pregnancies. Dr. Lindley was wonderful. She answered all of my questions, listened to me and was very caring. I am grateful to her and her staff for helping me through both pregnancies.”

The Center for Women’s Heart Disease helps monitor and guide women with congenital heart disease (CHD) into motherhood

Dr. Lindley leads the Center for Women’s Heart Disease, a clinic for women with heart disease who want to become pregnant.

“Women with CHD can safely carry a pregnancy,” says Dr. Lindley. “It is true that they may have a higher risk of complications, but we know how to screen for them, and each patient is cared for by a team of doctors who work closely together for a healthy outcome for mom and baby.

“Ideally, a planned pregnancy with a safe and effective birth plan is what we look for,” says Dr. Lindley.

“The patient sees a high-risk obstetrician and we talk to the patient about what possible complications she might have and when to go to the hospital. We have a plan in place well before the delivery of the baby,” Dr. Lindley says, “and we monitor the moms closely in the hospital and after delivery.”

Dr. Lindley says many of patients she sees at the Center for Women’s Heart Disease have more than one baby. But she notes how important it is for these women to be followed closely.

“Women with heart disease should be evaluated before becoming pregnant because the risk of any given woman is very unique and individual to her particular heart problem,” Dr. Lindley says. “We work very closely with the obstetricians at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital and take a team approach to these complex situations.

“We really take outstanding care of our patients,” she adds.