When do we offer a lesionectomy?

Structural abnormalities in the brain may cause seizure activity. These lesions can be congenital or acquired. Congenital lesions include malformations of the brain, such as cortical dysplasia—caused by abnormal brain folding or cellular migration during fetal brain development—or vascular malformations, arteriovenous malformations, angiomas, and cavernous malformations. Acquired lesions include brain tumors such as ganglioglioma and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (DNET); brain injuries; and infarctions and strokes.

When these structural lesions cause seizures, removal—or resection—of the lesion may result in relief of seizure activity.

After a thorough noninvasive evaluation by our comprehensive Epilepsy Center using tests such as high-resolution MRI, functional MRI, electroencephalogram (EEG), video EEG analysis, magnetoencephalography (MEG), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, we may offer a surgical plan including a lesionectomy. During a lesionectomy, the neurosurgeon will use leading-edge MRI guidance, or in some cases, intraoperative MRI, to target and remove the lesion responsible for the seizures. The surgical plan is highly tailored to the patient, the lesion, and the lesion location.

Lesionectomy: What to expect

- In a typical lesionectomy surgery, the child is admitted to the hospital the morning of surgery.

- The operation is performed under general anesthesia and usually takes several hours.

- A temporary window through the skull is made by the neurosurgeon.

- The lesion is removed using special instrumentation and techniques.

- The temporary bone window is replaced and secured, and absorbable sutures are used to close the incision.

- Typically, recovery includes an overnight stay in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), followed by two to three days on the neurosurgery/neurology ward on the 12th floor.

- Often, your child will have a postoperative MRI while in the hospital. Follow-up visits include a check with the neurosurgeon one to two weeks after discharge, and at six-month intervals thereafter.

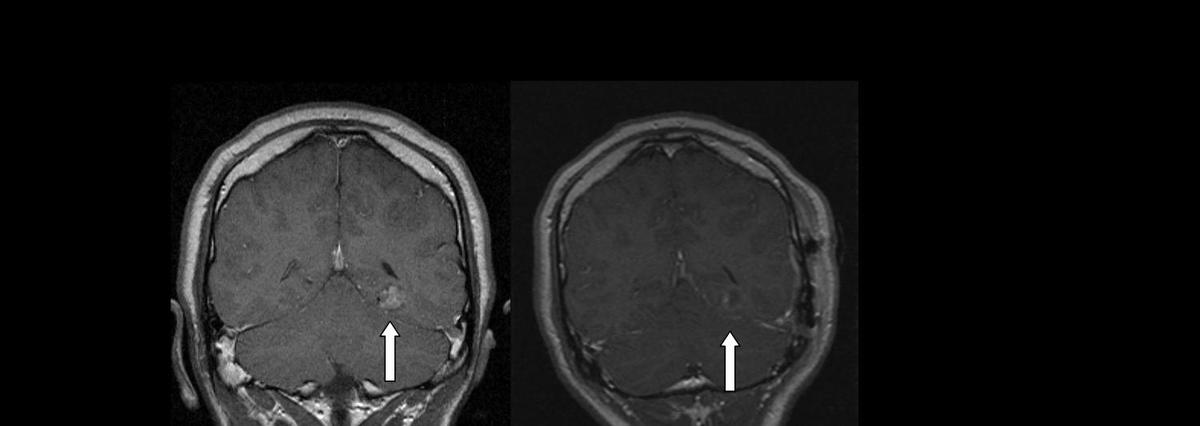

Lesionectomy image (before and after)