This summer, Gabby Carter played on the beach. She waded into the ocean. She spent hours some afternoons in the pool. Her summer included activities that would seem normal to any 7-year-old. But, for Gabby, they were extraordinary.

This summer, Gabby Carter played on the beach. She waded into the ocean. She spent hours some afternoons in the pool. Her summer included activities that would seem normal to any 7-year-old. But, for Gabby, they were extraordinary.

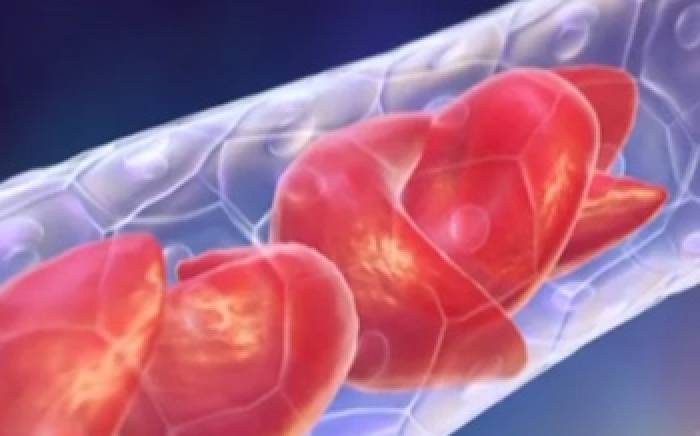

Last summer, Gabby was a very sick little girl. She was born with sickle cell disease, an inherited blood disorder that causes a change in the shape to red blood cells. The misshapen cells, which look like crescents, caused her blood to move less efficiently through her body, depriving her organs of oxygen, causing intense pain and putting her at high risk for stroke.

“For Gabby, we knew it was just a matter of time before she would have a stroke,” her mom, Debbie Carter, remembers.

By the summer of 2012, the road for the Carter family had already been a difficult one. Gabby was diagnosed with sickle cell disease when she was just a baby. When her daughter was 10 months old, doctors told Debbie how the future would likely look. She knew the odds Gabby would suffer through pain crises and anemia.

The family spent months in and out of St. Louis Children’s Hospital, managing the symptoms of Gabby’s disease. In November 2011, she had to start monthly blood transfusions due to narrowed blood vessels in her brain, a risk for future strokes. Then came hope –an anonymous donor was a good bone marrow match, and a bone marrow transplant was the best option for treatment. Gabby was 5 at the time.

“This was what we were waiting for. This was her shot at a cure,” says Debbie.

But the donor decided not to go through with the procedure, leaving the Carters looking at other possibilities.

“We had another option,” says Dr. Shalini Shenoy, director of the Bone Marrow Transplant Program at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “We found a cord blood product that was a suitable match for Gabby in the cord blood bank.”

At that point, Dr. Shenoy was leading a 10-center experimental cord blood transplant study, and had received approval to transplant three sickle-cell patients with unrelated (non-sibling) donor cells. Until this point, the preferred source for donor cells had been a patient’s brother or sister. Dr. Shenoy first discussed the possibility of a stem cell transplant with Debbie when Gabby was 3.

“She told us people had been cured from sickle cell with stem cell transplants.”

Dr. Shenoy also described a process that would be far from simple.

“They’ve been through their disorder, so they know what they’ve gone through. We explain to them the time period over which these transplant complications can occur, and help them understand what the pluses and minuses of transplant are going to be, and let them think about it.”

With the best chance at a bone marrow transplant off the table, though, Debbie decided to move forward with a cord blood transplant.

“It was the possibility of a cure. I couldn’t NOT do that. I had to give her a chance.”

Gabby spent the entire summer of 2012, from June through August, in the hospital. She received her transplant, then stayed in isolation to protect her weakened immune system. Even when she left the hospital, she couldn’t go home to Cape Girardeau, a three hour drive from St. Louis. She battled challenges inherent to transplant: hypertension, diabetes, and general sadness. But by winter, she was home, and turning a corner.

Children with sickle cell experience pain in extreme temperatures. But in December, she played in the snow for the first time—and didn’t complain of any discomfort. In January, she went back to school. And by summer, all signs of sickle cell disease had vanished.

Debbie continues to marvel at all of the seemingly small changes, “She’s doing things I never thought she’d do. She’s a normal kid. Her meds alone used to be a full time job. I spent all but two waking hours getting them ready.”

The care routine that had Debbie out of bed at 6:00 a.m. and up until 1:00 a.m. is now vastly different. Gabby takes six medicines instead of twelve. She can play without resting several times a day. She’s looking at a future with far fewer hospital visits, and a future without the constant fear of stroke. That alone, her mother says, has made the challenges of the last year worthwhile.

To Dr. Shenoy, Gabby’s progress is exciting in-and-of-itself, but it also holds enormous promise for one of the ways in which sickle cell disease can be treated and cured in the years to come.

“In the future, if we can say that transplant is going to be a breeze, we know how to deal with it, the outcome is going to be good, we can actually offer a cure for sickle cell disease patients across the board. That’s got a long way to go, but we’re working towards that process.”